Thoughts of Mastering Genealogical Proof: Chapter 3 Thorough Research

Posted: 15 Mar 2014 Filed under: Genealogy issues, Genealogy resources, Research strategy | Tags: archive catalogue, family history, Family History Library, FamilySearch, genealogical proof, genealogy, index quality, MGP2, reasonably exhaustive search 5 Comments

A reasonably exhaustive search is complete when you have sufficient evidence to draw a conclusion. That may be just two independent sources. It certainly does not mean finding every record in existence. Consider:

- How long are you going to live? Vampires would be excellent genealogists if it weren’t for the blood sucking obsession.

- Do you sleep, eat, and have a life besides genealogy (recommended for health)?

Figure out which sources are most likely to yield information pertinent to the research question. To do that you need to educate yourself about the time, place and record types. Bibliographic and archival catalogues are the keys that unlock knowledge.

Archive versus Library: FamilySearch is neither

I asked fellow panellist and archivist Laura Cosgrove Lorenzana to explain the differences between libraries and archives, because it helps us make best use of them. She supplied a helpful article from the Society of American Archivists that sums it up nicely. In summary:

| Library | Archive | |

| Typical Holdings | Authored works e.g. BooksDerivative records e.g. Published transcripts and indexes | Original records e.g. manuscripts, letters, photographs, artwork, books, diaries, artefacts etc.,Derivative records e.g. Indexes, finding aids |

| No of copies of items | Multiple, replaceable | Unique, irreplaceable |

| Objective | Current use | Preservation, current and future use |

| Access | Open, often borrowable | Restricted, handling conditions |

| Arrangement/ organisation | Subject classification.Catalogue has single or few levels, searchable by author, title, subject | Arrangement (logical classification) reflects provenance, relationships to other records, and preservation history.Catalogue has multiple levels, complex searches may be possible |

The Family History Library (FHL) in Salt Lake City, Utah, USA does not fit either the library or archive categories, and is a rather unique institution. It is a microfilm library. The microfilms contain copies of archival materials, transcripts, indexes and authored works. Each microfilm is identified by a number, which is needed to access information of its contents in the catalogue.

Photographic technology of the 20th century has shaped the FHL holdings. Traditional chemically processed film came in a linear strip forcing records to be copied in a fixed sequence. The costs were relatively high, an incentive to use all of each film roll, breaking away from the archival arrangement of records in the process.

So, the Family History Library is a strange hybrid based on old technology, and its offspring, the International Genealogical Index (IGI, on microfilm and later online) and FamilySearch databases reflect that history. The ease of access of these resources is commendable, but it has influenced the thinking of many genealogists and family historians spreading widespread misconceptions of research processes.

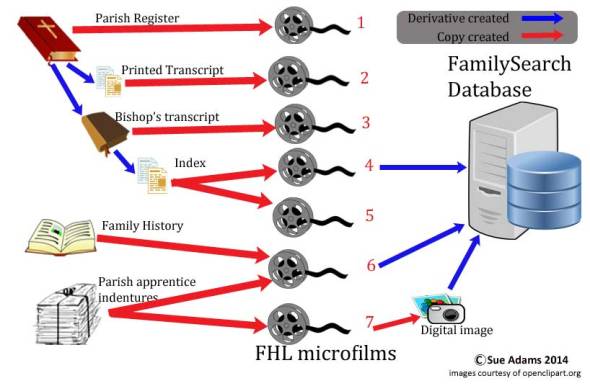

The processes leading to the microfilm and online resources relevant to the birth of an ancestor born in the early 1800s in England might look like this:

Note that the FHL catalogue records film details, with varying quality of provenance information. Note also only some microfilms have been indexed and incorporated into the FamilySearch databases.

Catalogues

An archival catalogue is the most important product of the processes performed by archivists in managing the collections in their care. At risk of making Myrt cry again, I repeat my message from the hangout-on-air:

The archival catalogue is a foundation of research. Without it, records cannot be found, and without the information it contains, the nature, relevance, provenance and quality of records cannot be assessed.

In the course of our research, we each build a personal collection. So, I recommend building a catalogue as explained in Provenance of a Personal Collection – Archival Accession, Arrangement and Description. The Community Archives and Heritage Group gives helpful guidance for small archives. Genealogists need a user-friendly cataloguing tool that integrates with all the other software we use.

Recent acquisitions that have not yet been catalogued, catalogues that are not on-line, or not computerised all pose challenges to finding sources. Archival catalogues describe hierarchical groups of records, but often are not complete down the level of individual items. A competent genealogist takes account of these difficulties and records what was found in the catalogues consulted.

Tools for finding information contained in sources, called finding aids by archivists, include indexes, and databases.

Index Quality

Thorough research is accomplished by targeting the sources most likely to contain relevant information. Then, search within each source for the information. Have you got that?

Yet all major genealogy websites default search covers all sources. This numpty scattergun approach serves no-one well and encourages poor habits. In Kerry Scott’s nutrition analogy, it leads to a diet of poptarts rather than a healthy balance, resulting in a rickety family tree.

Even carefully compiled indexes contain errors. It is fairly easy to spot index data that is clearly inaccurate such as gobbledygook rendered by optical character recognition (OCR). No search algorithm or fancy programming can overcome such poor quality data. More subtle errors are harder to detect. Before we can hold vendors to account, we need to know what error rate renders an index unfit for the purpose of a reasonably exhaustive search.

A competent genealogist takes steps to overcome the quality issues of indexes, databases and other finding aids.

Genealogy and family history research depends so much on archival material, even if it is accessed in derivative forms. So, take time to understand the work of archivists.

Such a thoughtful post. Thanks for sharing. I really liked the diagram and table you presented as part of the post. They helped make it all very clear. And it’s really helpful to compare the holdings of libraries and archives like that.

LikeLike

Very nice article Sue 🙂

LikeLike

Hi Sue,

Lovely blog post about chapter 3! In particular I liked your infographic about how England’s parish records make it in various forms to be held by the Family History Library. Regarding its status as a library, I was very sad in January 2013 to see its stacks of family histories and genealogies being removed and sent to deep storage as they were being digitized. It is great that the books can be viewed digitally, but nothing, oh nothing, replaces a book in hand.

Thank you for the links for archiving our collections. Nice!

Jen

LikeLike

Sue – First of all – great post! I have been following along with the panel each week. I was on the first panel and even so, I have learned something new each week with your group.

Second – The Family History Library in Salt Lake City is not only microfilm. They have 3 floors of books that have not been digitized or filmed.

I look forward to next week’s discussion on citations!

Sheri Fenley

LikeLike

[…] Thoughts of Mastering Genealogical Proof: Chapter 3 Thorough Research […]

LikeLike